In these emerging ideas pages I re-examine some important research about assessment and feedback in the published literature through the lens of comparison. The intention is to identify supporting ideas and to exend, complementor sometimes critique them by making comparisons with comparison-based ideas themselves. In effect, I am practising what this whole site recommends, which is to generate inner feedback and understanding through making comparisons and to make that inner feedback explcit in writing and through discussion.

NOTE: Everything on this website is Open Access distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work and source are properly cited. This website is maintained by David Nicol.

Principles of Good feedback practice: initial thoughts on revision

In 2006, Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick outlined seven principles of good feedback practice that if implemented would enable students to better regulate their own learning, that is become more confident and autonomous in their ability to process feedback information from others and to generate their own feedback. The principles are reproduced here.

Good feedback practice:

- helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards);

- facilitates the development of self-assessment (reflection) in learning;

- delivers high quality information to students about their learning;

- encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning;

- encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem;

- provides opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance;

- provides information to teachers that can be used to help shape teaching.

Reference: Nicol, D. & D. Macfarlane‐Dick. 2006) "Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice" Studies in Higher Education, 31(2) 199-218,

Given my more recent work on comparison-based feedback, some people have asked me if I would revise these principles or if they still stand. This is a difficult question as there are new premises underpinning my new research - for example that comparison is central to all feedback processes and that the missing ingredient in all thinking about feedback is a neglect of the fact that students are generating feedback all the time, even when there are no comments or dialogue. It seems that scholars, some time in the past just decided that feedback is the comments that teachers (and more recently that peers) provide and they have mostly ignored how students generate feedback from resources, as they are engage in a task and pursue their own learning goals, albeit guided by the task instructions. However, given that I am not ready to provide a completely new set of principles, and that some of the old principles do still stand (e.g. that feedback dialogues are important) here is my first attempt at a revised set. The main thing missing for me is that I do not use the word comparison in this set especially given that comparison is the pivot upon which all feedback is generated whether by teachers as comments for students or by students themselves. However, maybe it is not necessary to put the mechanism inside a set of principles as these are meant to be at a high level.

So here goes

Good assessment and feedback (Nicol, 2021):

- Helps clarify learning goals and expectations

- Activates students as self-assessors and generators of mindful self-feedback

- Activates teacher and peer interaction and dialogue as opportunities for feedback generation

- Deliberately utilises artefacts/resources as information for students’ activation of self-feedback (e.g. documents, videos).

- Makes tangible (explicit) the outputs of self-feedback (in writing, discussion, action)

- Encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem (by increasing student agency for in feedback processes).

- Provides diagnostic information to teachers that can be used to help shape their feedback decisions.

I would be very interested in any comments anyone has on these, as they are for now a 'work in progress'.

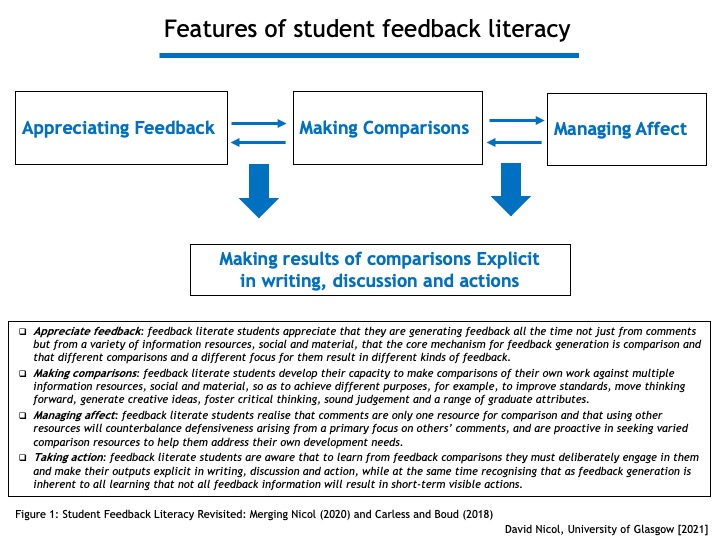

Student feedback literacy

Synthesising ideas from Carless & Boud (2018) & Nicol (2020) the following is my attempt to present an updated model of ‘student feedback literacy’. This reframing opens up significant new possibilities for the design of feedback practices

Dialogue and Student Feedback Literacy Reconsidered

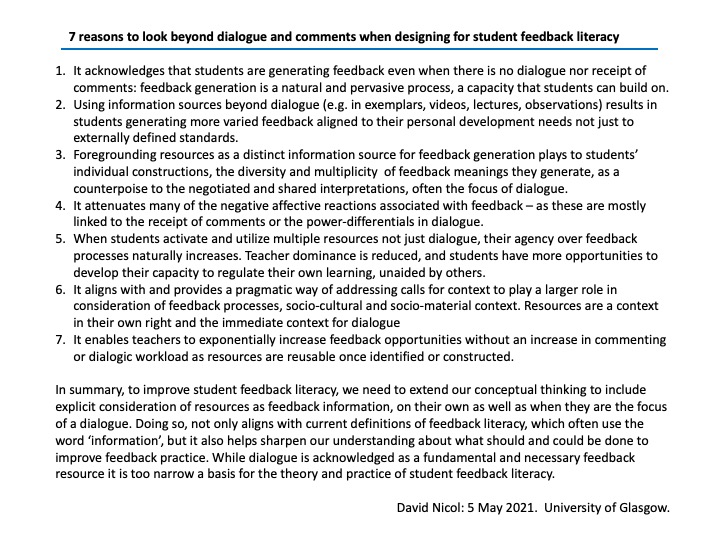

In Carless and Boud's (2018) article on student feedback literacy they claim that their thinking is founded on a social constructivist persepective and on the notions of dialogue, sense-making and co-construction. One implication of my extension of their model as shown above is that we need to widen our concept of feedback and not just view it as driven by the communciation exchanges, by comments and dialogue. Others writers like Gravett (2020) and Chong (2020) and Esterhazy (2019) have already made this case, in their arguments that context -sociomaterial and ecological context - should play a bigger role in feedback literacy thinking. However, Gravett and Chong take a very wide view of what might comprise context making it difficult for teachers to identify easily what are the most important aspects of context to focus on in practice settings. Esterhazy (2019) on the other hand believes it is important to view dialogue as occuring in a context, as not occurring in a vacuum, and she sees dialogue and context as inter-active and intermingled in practice. I subscribe to her veiw but also suggest that resources on their own can be used by students for feedback generation independently and alone even when there is no dialogue. What is of interest in the briefing below is resources as context - such as written documents, lectures, rubrics, online resources of any kind, audio, video and textually interactive, peer works or exemplars. I do not deny the existence of the wider context of the institution, the course, the classroom, the tools and artefacts used during learning. However, resources as context for learning and feedback generation should certainly be considered by any teacher. They might be said to comprise the proximal context for learning while the others are the distal context, not in terms of a spatial dimension but in terms of accessibility, immediacy and relevance to learning and learning improvement. The most important idea below is to look beyond dialogue and comments and to consider the role of resources separately and in combination when designing for feedback and trying to promote feedback literacy. Other briefings to come will provide 'seven principles of feedback design' and 'seven reasons why we should think of comparison as the core mechanism for the generation of feedback'.

Self-Assessment

Researchers writing about self-assessment suggest that the first step is that (i) teachers define the criteria by which students assess their work (ii) then teach students how to apply the criteria and (iii) then give them feedback on their self-assessments (e.g. Panadero, Brown). The merit of this is that if students have a good understanding of the requirements for some work as defined by the criteria then they can assess their progress in meeting those criteria by themselves and improve their performance. This could enacted as a formal process where students self-assess after producing some work (maybe a draft) and then update it or they might submit a self-assessment with their assignment. Usually it is an informal process left to students after they have had experience in applying the criteria in a workshop usually before they begin their own work.

In my recent article (Nicol, 2020) I have made the case that self-assessment is a process that relies on comparison and that the output of such comparisons is that students generate inner feedback. Panadero, Lipnevich and Broadbent (2019) take the similar postion with regard to feedback, maintaining that self-assessment results in students producing self-feedbak. However, these researchers have not identified comparison as the process underpinning self-assessment. Nonetheless if we link these ideas together it could be argued that more could be leveraged out of self-assessment in terms of feedback if we expanded the range of comparators beyond criteria to include other information. The following example will clarify where I am going with this.

Self-assessment [comparison] and feedback generation

Imagine a medical student on clinical placement who might assess a patient and devise a management plan for the treatment of a disease. After doing this, she is asked to compare her plan (i.e. self-assess) against some consultant plans or to the plan that was actually enacted. From this she would generate feedback about the quality of her own plan. She might however compare her plan with both the consultants' plans and against some criteria given by her supervisor. This multiple comparison might lead her to generate better feedback on the quality of her plan and develop a language for talking about the qualities of treatment plans.

What if instead the medical student is asked to compare her management plan against the management plan for a similar clinical condition but that has a different underlying pathology (eg pulmonary embolism and pneumonia both of which a patient might present with shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain). Then she would generate feedback about the similarities and differences in these pathologies and about how these similarities and differences alter the management plan.

Or she might instead compare her management plan against that created by an allied health care worker. Out of this she would generate feedback about how the plans align or not and about some considerations with regard to collaboration and coordination, important in the health professions. These examples are depicted in the figure below and thanks to Susie Roy and Tim Fawns for giving advice regarding whether this example would work in Medicine.

Another merit of this approach can be highlighted by considering a recent article by Winstone and Boud (2020) in which they suggest that we disentangle assessment from feedback processes. The reason they give is that by doing this we can think about ways of amplifying feedback opportunities without increasing high stakes assessment workload for teachers. Also we can then consider how we might help students learn more broadly without corralling all learning towards getting good grades. From a feedback comparison perspective for example we could stage different and varied kinds of information for comparison or self-assessment across the timeline of a course without all of them being criteria. This would make the students' learning more interesting, as comparison-based feedback activities are engaging. This is not about abandoning criteria it is about recognising that criteria have a specific use but that other information for self-assessment will yield other learning outcomes, for example, important graduate skills useful beyond university.

Authentic Feedback

Another argument in the current literature is that we should engage students in Universities and Colleges in feedback practices that mimic how feedback operates in professional practice. This is the argument for authentic feedback (Dawson, Carless and Lee, 2020). The idea is that feedback processes will then be better, and students will be more effectively prepared for the world of work, although that is not the only reason for doing this. The assumption is that how feedback happens in professional and employment settings is more natural than how it happens in the university. However, this does raise the question of what we mean by natural. Students are naturally and spontaneously generating feedback all the time from different information sources: and comments are only one source of information for comparison. Also, there are usually multiple comparisons going on rather than a single comparison even when students use comments. So building on authentic feedback might be framed in terms of builidng this internal feedback generating capacity rather than emulating feedback practices in employment settings as the natural comparisons in these settings have yet to be harnessed and capitalised on. As in current higher education, they usually centre on dialogue or, in terms of the framing here, in dialogical comparisons rather than both social and material comparisons. So perhaps higher education has something to teach those in professional practice about authentic feedback. I am not arguing that we cannot learn from professional settings only that those in the professions might themselves have something to learn about how to develop authentic feedback practices.

Naturalness of Inner Feedback Processes

When I say that creating inner feedback is natural, ongoing and pervasive (Nicol, 2020) I am not saying just that when students produce some work that they might compare it with similar works. This is how some have interpreted my position. Yet my argument is that anything might serve as a comparator for students and that these comparators will be chosen by them. Yes these choices will be influenced by what they think the task requirements are, their own goals and the environment they inhabit. However, the point I wish to make here is that students might compare their work against criteria or ideas or concepts they have formulated before or againt the lecture notes they created. What they use for comparison has not been researched. Hence, I am taking an even much wider sweep than cognitive researchers on comparison who have mainly focused their theories and work around analogical comparisons. For example, they say that when someone intends to buy a car they will compare the car in front of them with other cars in the showroom but also against their internal idea of the car they want. I say they might also have a list of desireable features written or in their heads (e.g. I would prefer a black car, it must have heated seats) and they willl make those comparisons as well, simultaneously or sequentially, consciously or with less conscious awareness. I call the latter analytical comparisons. Both analogical and analytical comparisons generate inner feedback and from my research and that of others we can say that different kinds of comparison information lead to different kinds of feedback (Nicol and McCallum, under review, Lipnevich et al, 2014). Hence the possibilities for teachers wishing to expand feedback possibilities an in turn students' learning from them is vast. They can ask students to compare their work against literally anything if it has educational value and it might generate productive feedback. So I could ask students to compare some an essay written on Piaget specifically with the principle of scaffolding written about by Vygotsky.